It seems that the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline, which is being built on the bed of the Baltic Sea, will be finished at any cost,irrespective of the steps the US is taking on sanctions and possible difficulties for theoperating companythat are linked to this. Permission for laying the pipe has not yet been obtained from Denmark, but the receiving station in Lubmin is already being expanded – the Audacia vessel has been working on Germany’s Baltic coast since the beginning of October. The station needs to be equipped with two new large valves; robots will then pass through these from the Russian side into Germany to inspect and clean the pipes. They will automatically collect data about the condition of the pipeline over a length of 1200 kilometres, the approximate length of the pipe. It is expected that around 40 kilometres will have been laid in German waters by the end of the year.

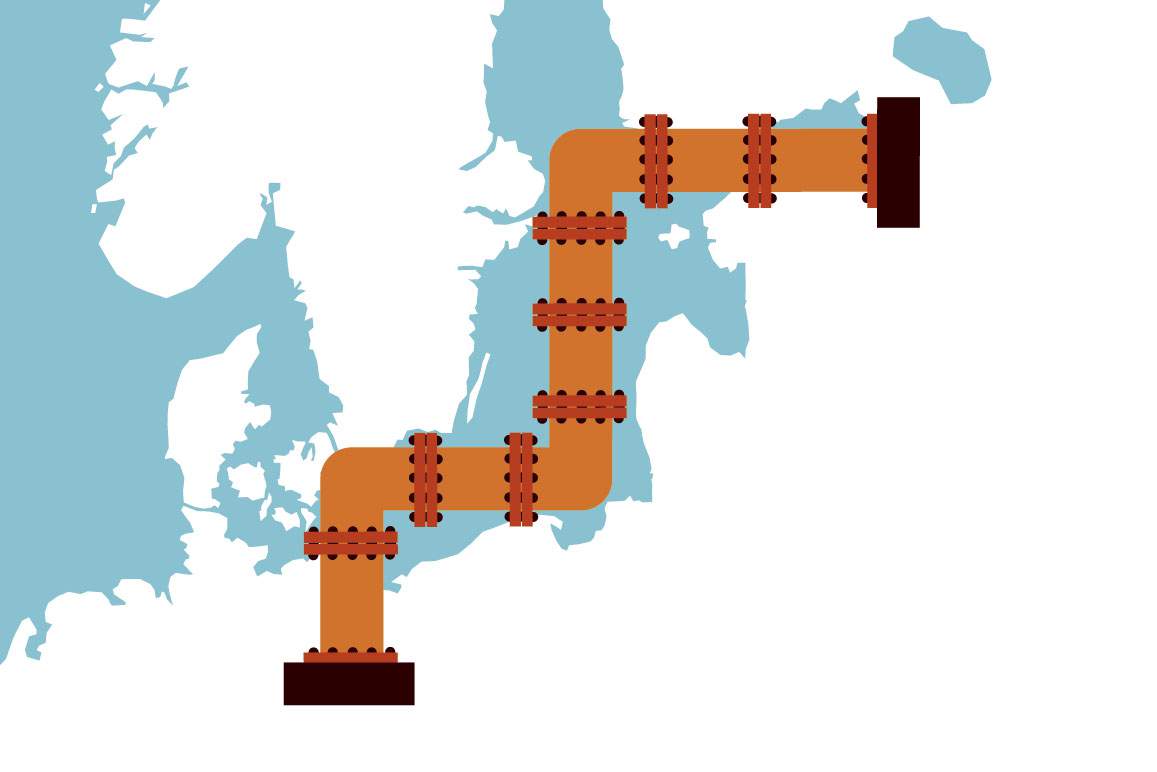

The Nord Stream 2 marine gas pipeline, with a capacity of 55 billion cubic metres (bcm) a year, should run through from the Slavyanskaya compressing station in the Kingiseppsky district in Leningrad Oblast to Germany’s Baltic coast.

Gazprom is the founder of the Nord Stream 2 joint-stock company and has a controlling financial interest in it. The construction consortium also includes the French energy concern Engie; Austria’s OMV; the Dutch oil giant Royal Dutch Shell; and Germany’s Uniper and Wintershall companies, the former being the subsidiaryof energy giant Eon, and the latter a subsidiary enterprise of the BASF chemical concern. The length of the pipeline is 1230 kilometres; gas should start to flow through it into Germany by the end of 2019. The total cost of the project is around 9.5 billion Euros.

From the point of view of business and the German economy, the project is a more than successful and necessary enterprise; this is something pointed out not just by Germany, but in particular by Austria. On the political level, the project is running into active opposition from East European countries such as Poland, Ukraine and the Baltic countries, which fear losing opportunities to receive transit fees for Russian gas flowing through their territory into Europe. The project does not bring them any economic benefits, and so they view it from a purely political, and even geopolitical point of viewas asserted by the Lithuanian President Dalia Grybauskaitė. Critics also point to the political aspect and say that the project places the EU – primarily Germany – in a position of great dependence on Russia.

Germany, it turn, continues to consider Nord Stream 2 an exclusively economic project, which in no way speaks of dependence on Russia. German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas states that such a dependency simply does not exist. In her turn, Chancellor Merkel is aware of critical opinions, but considers the project significant and important for Germany: considering Germany’s diversified gas market, dependence on Russia is not a threat in her opinion, but it is expected that consumption of gas in Germany in the coming years will only grow.

In fact, Germany gets its gas not only from Russia, but from Norway and the Netherlands. But Berlin insists that Ukraine should not be adversely affected: in the future, Ukraine must remain a transit route for EU countries. To this end, a negotiation process between Ukraine and Russia has been launched, mediated by European Commissioner Maroš Šefčovič, who has responsibility for energy questions. Granted, he has not got particularly far yet.

Apart from pressure from East European countries, according to certain data, there is an even more powerful pressure, namely from the US, which wants to supply its liquefied natural gas (LNG) to the EU. All this pressure currently falls on the small northern European nation of Denmark. Precisely because of this, the application for permission regarding Nord Stream 2, which was submitted to the Danish authorities in April 2017, has still not been approved. Nord Stream 2 will go through the territorial waters or exclusive economic zones of Scandinavian countries located along the shores of the Baltic Sea, including, Finland, Sweden, and Denmark. Of these countries, it is from Denmark alone that the operating company has not so far managed to obtain permission to build, although usually this permission is given within year at most. Not in the case of Nord Stream 2, however.

Nevertheless, the business consortium does not plan to give up and has already worked out an alternative route 174 km long, north of a Danish island. A corresponding application for permission to build was submitted in August 2018. According to the plans, about 87 kilometres of the gas pipeline should go through the territorial waters of Denmark’s exclusive economic zone to the north-west of the island of Bornholm. The scrutiny process for permission to build should conclude on 12 December, but its outcome is unclear so far: the fact that the direct route has not been approved does not mean that the alternative will automatically be approved. It is expected that public hearings on the construction plans will take place on 14 November in the Bornholm region of Denmark.

There is another possible obstacle besides that in Denmark, initiated by the US, namely sanctions they have threatened. The US’s opportunities here are wide: they could, for instance, place restrictive measures on banks involved in the construction, or on companies producing pipes for the pipeline. If this happens, the project will become substantially more expensive and might even be halted. Many German politicians appear to believe this unlikely, however. Firstly, in their opinion it is far more economically and environmentally beneficial to supply gas through the pipeline from Russia than as LNG from the US. Secondly, the opinion is voiced in Berlin that potential American sanctions against the companies participating in the project will not be able to hinder it.

Representatives of the operating companies are in any case resolute and are not planning to go into reverse.As well as former German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder, there is another former minister on the consortium’s side – former Austrian finance minister Hans Jörg Schelling. Both ex-ministers are acting as consultants. The authorities are also resolute: Andreas Michaelis, State Secretary in the German foreign ministry, for instance, declared that he does “not want European energy policy to be decided in Washington.” At the ministry, they think that the US Democrats may use the question of European sanctions against the gas pipeline as a weapon against President Trump, to whom ties with Russia were attributed during his election campaign. Thus, Berlin does not want Nord Stream 2 to become a bargaining chip in American domestic politics – and this means that Nord Stream 2 will still be completed.