Last Christmas, Santa Claus brought the Westinghouse Corporation exactly the present it was wishing for. This could have been a fairytale ending if only the world’s greatest nuclear energy experts had not expressed scepticism about this “present” by Easter.

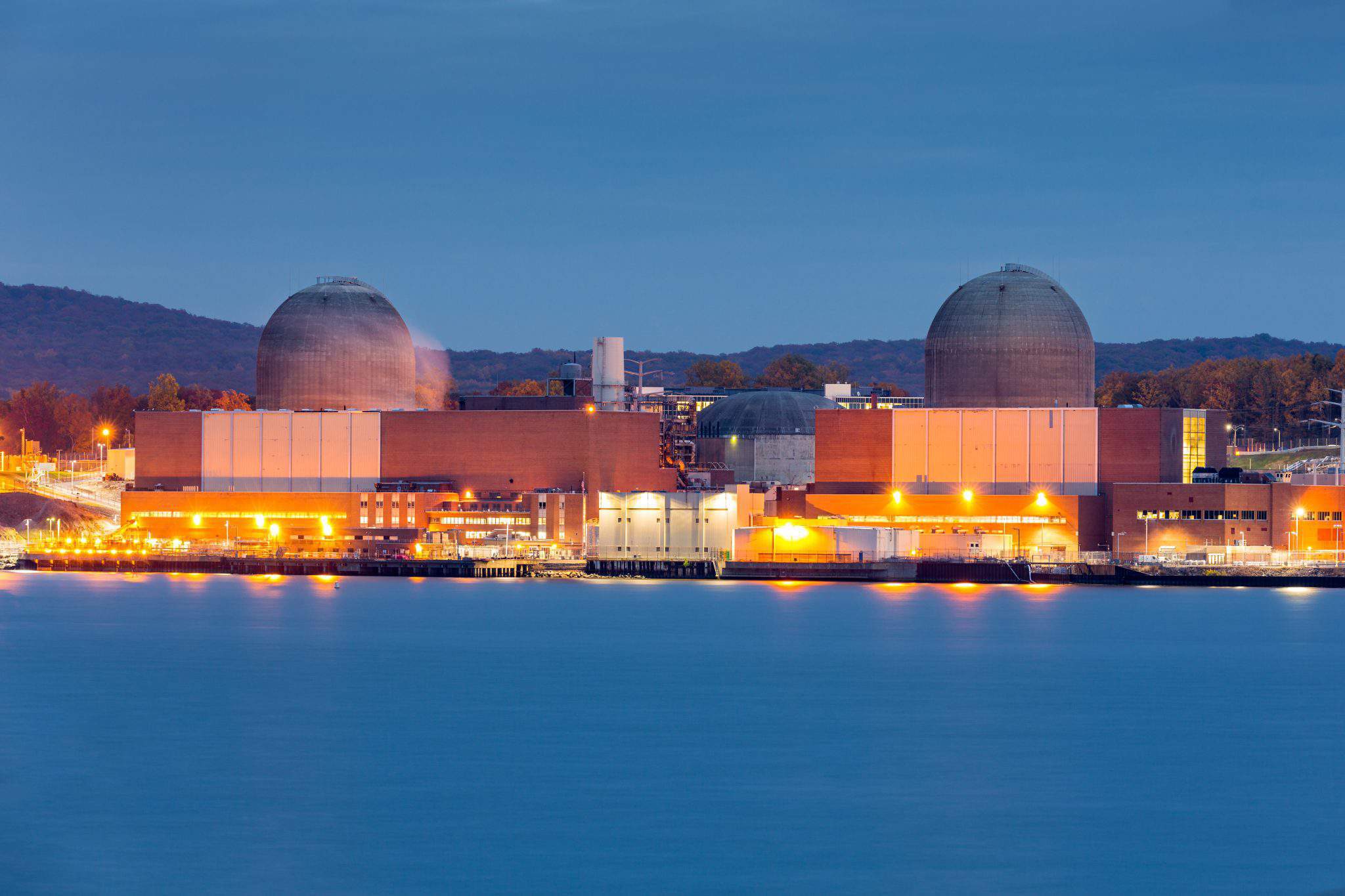

Nuclear power plant on the Hudson River, north of New york City

Westinghouse, the American subdivision of Japan’s Toshiba specializing in the production of nuclear reactors for power plants had already long since gone into bankruptcy. Finally, the Brookfield Business Partners management company, headquartered in Toronto, announced just before New Year that it was ready to buy the American reactor subdivision from Toshiba for $4.6 billion. Just a few days before this, Brookfield had struck a deal to buy SunEdison’s TerraForm Global Inc for $750 million. In an instant, these large-scale investments transformed Brookfield into one of the largest players in the global market for managing intellectual projects. The Canadians hurriedly issued a press release timed to coincide with the purchase of Westinghouse in which they called their acquisition a “significant American company” and underlined its “strong market position.” It was precisely the attractive income and funding stream profile that was decisive in the decision to buy Westinghouse.

According to market analysts however, euphoria about the mutually beneficial deal, as Brookfield and Westinghouse see it, could pass very quickly. The drawn-out bankruptcy procedure announced a year ago and the change of owner of the Westinghouse Corporation do not bode well for the company’s ability to fulfil the contractual obligations it has assumed to build reactors and supply fuel for nuclear power stations. The clearest illustration of the critical state of affairs in Westinghouse is the rejection by VC Summer, the owners of nuclear power stations in the US of its services in building two AP1000 units, due to the date for commencing operation being constantly put back (by six and then nine years) and the increase in the cost of the works – by 75% of the original cost. Westinghouse could probably regain control of the situation by reducing the cost of the project, but the new owner is hardly likely to do this, considering the volume of its investment in buying the company and its natural desire to begin to get its money back as soon as possible.

Nuclear power plant on the Hudson River, north of New york City

Saddest of all for Westinghouse and now for Brookfield is not just VC Summer declining to cooperate, but the way in which this has happened and the consequences that could ensue. Up until the moment that the contract was severed, that is in July of last year, something in the order of $4.7 billion had already been spent on building the reactors. According to American experts, the trouble surrounding the cancellation of construction of new units could bode ill for the implementation of a second project to build AP1000 reactors at the Vogtle nuclear power station site. And thus Westinghouse’s projects in the US itself could very soon be acknowledged as unprofitable and terminated.

In this situation, Brookfield has lost control over a standard administrative algorithm, a large part of which consists of public steps to integrate the new business project into the industry’s market structure. The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette informed its readers that the President of Brookfield had originally declared its lack of interest in implementing projects to build nuclear reactors in the US or abroad, but the company had later altered its position and “considers that the design and technology of the AP1000 is the core of Westinghouse’s activity.” “Brookfield will invest considerable funds in this direction” is how the latest formulation from Westinghouse’s new owner sounds.

It looks as though Santa Claus played a nasty joke on Brookfield and Westinghouse. There is only one possibility for a real return to the market for Westinghouse and that is serious investment in the development of the projects. But the Canadian investors were probably mistaken in their calculations of how much they would need to invest in developing Westinghouse. Covering costs connected to bankruptcy and buying a company is one thing. It is quite another not merely to manage its activity but to invest new billions with no clear plan of how to get one’s money back.