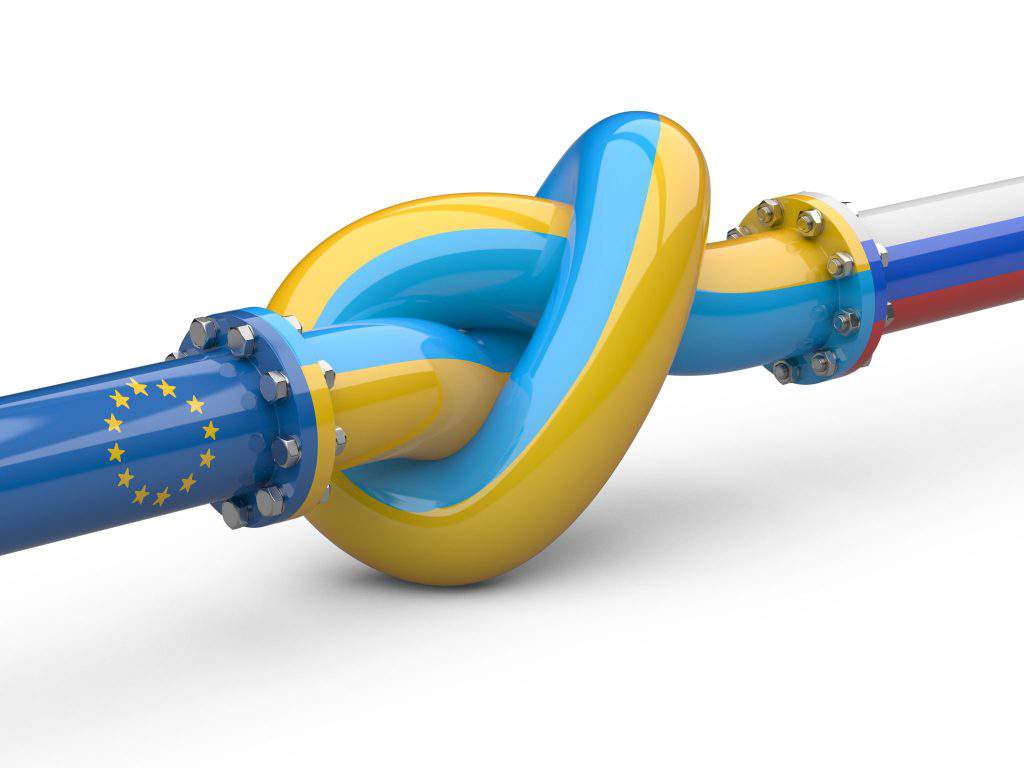

Despite the ending of the winter peak in fuel consumption in European countries, the situation with gas supplies to Europe via Ukraine remains acute; this is apparent not merely in the fact that from 26 February to 1 March there was a real threat of Ukrainian gas reserves falling below 8 billion cubic metres (bcm), which is considered the minimum level for allowing effective gas flow through Europe to continue – this demonstrated an absence of reserves which are a kind of technological insurance for the Ukrainian gas transport corridor, which remains key for ensuring gas supplies to EU countries.The acuteness of the situation is clear from the strategic dead end that has arisen in relations between Russia and Ukraine on the system for further use of the Ukrainian gas transit system (GTS) for transporting gas into Europe.

The Ukrainian GTS is one of the largest inter-regional pipeline corridors in the world, with a total pipeline length of more than 35,000 kilometres. On the border with the EU, its capacity is more than 140 bcm of gas per year. The development of this infrastructure actually began in 1948, when the Dashava–Kiev part of the gas transit system came into operation, and continued until 1990; it was an infrastructural priority for the Soviet Union as a whole. Even in the Soviet period, Ukraine did not possess resources of its own for creating such a system and carrying out major reconstruction on it.

The Ukrainian gas transport system is the last infrastructural object in Ukraine, other than Odessa’s sea port, which has if not global, then pan-European significance. Importantly, the replication and reconstruction of an infrastructural site on this scale would be difficult if not entirely out of the question in modern conditions, at least in the medium term.

Russia’s European partners have made a strategic mistake in their assessment of the prospects for how the situation regarding Gazprom’s use of the Ukrainian GTS will develop: in Europe, particularly in supranational structures, it was thought that Russia would take decisions on the future use of the Ukrainian GTS based principally on economic considerations – and that there were no circumstances in which Russia would completely stop the flow of gas through Ukraine. It was thought in Brussels that the Kremlin would use the threat of stopping transit exclusively as an instrument of political pressure on Kiev.

Now, however, there is a growing conviction in the European capital that Moscow has taken a principled decision not to use the Ukrainian GTS, despite the cost and political consequences of such a step. As a result, the European Union now has no starting position for the negotiating process with Russia that Moscow would consider acceptable, and such a platform cannot be formed until the EU returns to the position of honest broker between Russia and Ukraine. Even then, though, trust in the objectiveness of the EU will be seriously undermined.

The problem lies in the fact that as a result of crisis around EU mutual legal claims at virtually all levels – both national and pan-European – Brussels has completely lost its status as a natural intermediary between Russia and Ukraine. This applies not only to gas transit, but more generally. The EU has clearly defined its position as one of supporting Kiev almost unconditionally; this has unleashed significant political and economic processes in Russia the ultimate conclusion of which is very difficult to determine.

What first and foremost has not been understood in EU countries is that the notorious Ukrainian transit question does not just involve the possibility of transferring the burden of partially financing the ineffective Ukrainian management system to Gazprom; in essence it would mean transferring it to Russia. It is a question about European structures’ capacity to form a proper investment process around the Ukrainian gas transit system, which would at very least remove some of the anxiety and irritation from the Russian side. But instead of forming a system which could attract a wide circle of investment, both governmental and private, including security investment, Russia and Ukraine’s European partners have tried to reconstruct a levy system with a “transit tribute” in Kiev’s favour: this is known to be unacceptable not only to Gazprom but to the Russian state. No compromise option for solving the conflict has even been suggested.

Regardless of the specific outcome of the dispute between Gazprom and Ukraine’s Naftogaz about compensation – and Naftogaz plans to sue Gazprom for no less than $20 billion for what in Kiev’s opinion is the tariff having been set two times too low in the contract on gas flow through Ukraine – no investment processes surrounding the modernization of the Ukrainian gas transit system are envisaged for the near future, least of all any involving Russian capital.

The European Union has thus rejected the idea of being a co-investor with Russia in creating a favourableregime for renewing and supporting the effective functioning of the Ukrainian GTS –for example by directly compensating Kiev for difficulties in using the “take or pay” formula –and will be obliged to take the entire investment burden for the future of the Ukrainian GTS on itself. This is highly risky, if you take into account Kiev’s wish to continue its policy of confiscating Gazprom’s property within Ukrainian territory.

In general, this will mean significantly greater cost within a regime that is known to be opaque, especially taking into account the visible deterioration of the Ukrainian political system and management of its economy.

According to the most modest estimates, the volume of investment that European countries and businesses will have to make in preserving the operation of the Ukrainian GTS will be €10-12 billion in the period from 2020 to 2025, and that is on the assumption that the standard of corruption in Ukraine remains at the existing level and there is no further deterioration in the political system. It should be noted that if the pronouncements of Ukrainian officials are to be believed, supporting the ability of the Ukrainian GTS to function should amount to $200-300 billion in annual investments alone – which Ukraine is not planning to allocate. Furthermore, it is planned to preserve the highly opaque scheme for the expenditure of these funds and to ignore the non-economic risks, which are objectively growing.

After the recent decision of a Stockholm arbitration court that Gazprom should pay Ukraine compensation, there is in theory no option by which Russia would become a co-investor in a project to modernize the Ukrainian GTS.This is the case even if EU structures succeed for a time in blocking the Nord Stream 2 project and delaying progress on implementing extension of TurkStream to EU countries. This will entail great political and PR cost and damage to relations with Russia.

That is, as a result of politically motivated actions, mainly by European structures in questions of pan-European energy security and the energy security of the EU countries key to providing forward economic growth, a dangerous Catch-22 has arisen, in which any further move that Europe makes in the existing paradigm will threatens serious consequences. Attention should be paid to the fact that this situation has arisen at a moment when an active re-ordering in the global energy market is taking place and a new price war between hydrocarbon suppliers has not been ruled out – and this time, as President Trump’s actions demonstrate, it could involve political pressure.

For the EU however, particularly at a corporate level, the situation that has arisen around supplies of Russian gas through Ukraine and in general around the Ukrainian GTS, should become a very important lesson, undermining once more the great danger of taking political decisions in an economic context. This is especially so considering that an exceptionally difficult period lies ahead for the European Union, with the completion of a renewed regulatory mechanism in the sphere of energy security.