Copyright: Baltic Pipe Project

Whenever the Baltic Pipe project is mentioned, it is accompanied by the adjective “strategic”, to convey its importance. The project is a crucial part of extensive Polish ambitions to create a regional energy hub and to secure what Poland believes would be energy independence. It also enjoys the political and financial support of the European Union and will eventually make a significant contribution to its North-South Gas Corridor plan.

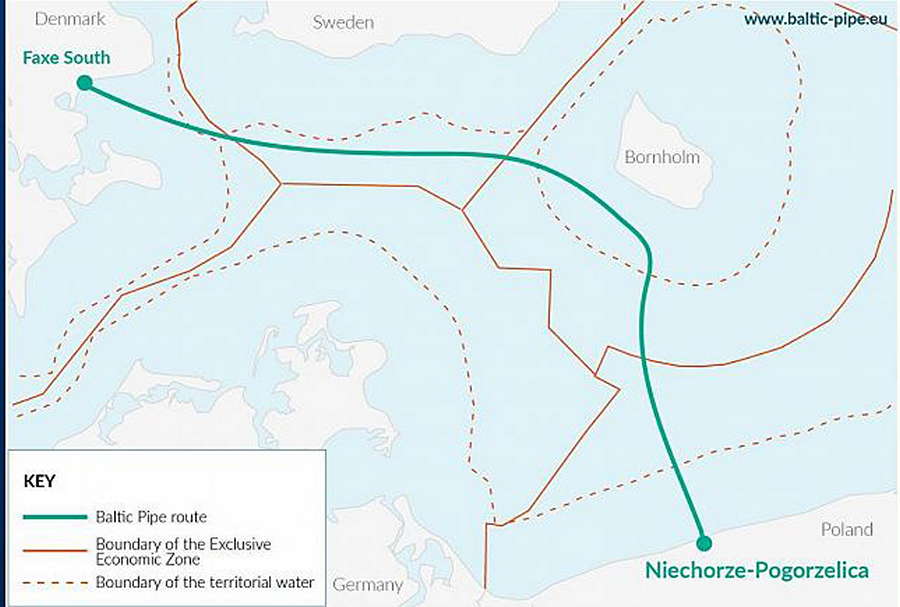

The Baltic Pipe, provisionally scheduled for completion by October 2021, will connect the Norwegian sector of the North Sea to Poland via Denmark. Its total gas transportation capacity is thought to reach 10 billion cubic metres (bcm) per year.

“This is really very good news for Poland, and not just for the near future, but I deeply believe for the coming decades,” stated Poland’s president Andrzej Duda, welcoming the news of a deal to build the pipeline.

However, the lofty goals set by certain politicians and experts and the high expectations nurtured by the media and the public will face the test of reality as Poland ultimately has to come to terms with the true costs of its aspirations.

In all complex projects, initial calculations never match final expenditure. Various unforeseen factors mean that costs invariably tend to grow and deadlines are put back. The Baltic Pipe is no exception, and it would be naïve to think otherwise. This poses the obvious question of the price that international investors and then local consumers will pay. But beyond this lies the apparently more important question of whether the project is capable of delivering on its aspiration of enhancing European and Polish gas market stability.

Capacity issue

For quite some time, Polish leaders have been dreaming of making their country more than just an importer of natural gas: they have believed the Baltic Pipe would enable their energy companies to grow stronger and to start exporting extra volumes to other countries. Last year, prime minister Mateusz Morawiecki even extended an olive branch to Germany, offering it gas supplies from the Baltic Pipe – although to no avail.

Polish state oil and gas company PGNiG initially expected that in the first year after the pipeline is completed, it would extract at least 2.5 bcm of natural gas per year from the Norwegian offshore continental shelf. But calculations have been revised downward greatly since then and the company now expects to extract only 0.9 bcm of gas per year from its fields.

This is more than twice below its own minimal target and seriously questions the financial rationale of the entire project which, even without such a negative re-assessment, has drawn scepticism from a broad range of Polish energy companies and some experts over the years. “A new pipeline is not necessary to manage gas exports,” said Oda Helen Sletnes, Norway’s ambassador to the EU, just five years ago.

Alternative routes

However, there are other solutions which Poland is probably considering right now. First, PGNiG may be thinking of trying to accumulate gas from its various projects into the Baltic Pipe. This idea is reasonable, but it would hardly resolve the overall capacity issue since all the fields it owns or is developing are fairly small and are unable to provide sufficient volumes either jointly or alone.

In 2019, PGNiG president Piotr Wozniak said in an interview that the project would give Poland “much cheaper” gas. But the truth is that the underperforming pipeline will instead create further headache for the wider public. Given its projects’ small reserves, the company will have to push prices up to cover gas extraction and transportation costs, adding to the burden on consumers, investors, and the economy.

Second, PGNiG may have hoped to contract nearly 1.1 bcm per year from Denmark’s Tyra field in the North Sea to transport it through the pipeline from 2023 to 2028. But the commissioning of the field after its redevelopment was delayed last year, raising the prospect of Denmark’s energy giant Ørsted being unable to fulfil its contractual obligations, at least in the early years of the period.

Third, there is an option for PGNiG to buy over 7 bcm of gas per year from its Norwegian counterparts to fill the pipeline. This, however, would not mean increased production, but rather a redirection of supplies from northern Europe and so the decision very much depends on the goodwill of other countries and companies.

Given all these obstacles, there is no reason to expect the project will proceed according to initial estimates. Moreover, this will not happen even in the most optimistic scenario. From today’s point of view, the only practical question is how to limit the losses of all parties and mitigate economic and political consequences.

The best is the enemy of good

The Baltic Pipe may look like the perfect solution for Poland’s energy ambitions but a rather different reality is now emerging from the rhetoric, which involves long lines of potentially empty pipes stretching from Norway to Poland and Denmark. The project will not bring new billions of cubic metres of natural gas to the European market. To be used at its full capacity, it will have to rely solely on the tricky feat of diverting the volumes it needs from other gas flows.

“The best is the enemy of the good” is a proverb that exists in many languages. The aphorism is commonly attributed to Voltaire, who quoted an Italian proverb in his Dictionnaire philosophique. Was it ultimately worth building a new pipeline if its primary function seems to be gradually being scaled down and limited to rearranging existing flows? Probably not. It will not reduce prices for households or wholesale buyers: most likely it will do quite the opposite. Finally, it is hard to see how it will enhance Poland’s energy independence.

Poland could have taken a different route and saved hundreds of millions of euros of European taxpayers’ and corporate investors’ money. It could have relied on the existing European infrastructure and bought gas from its closest neighbour, Germany, importing it through Frankfurt (Oder). This might not have been ideal politically, lacking the “independence” rhetoric of the Baltic Pipe project, but it would certainly have been good enough for companies and households and, surprisingly, for politicians too since it could have been achieved much more quickly and without embarrassing delays, higher bills and other issues.