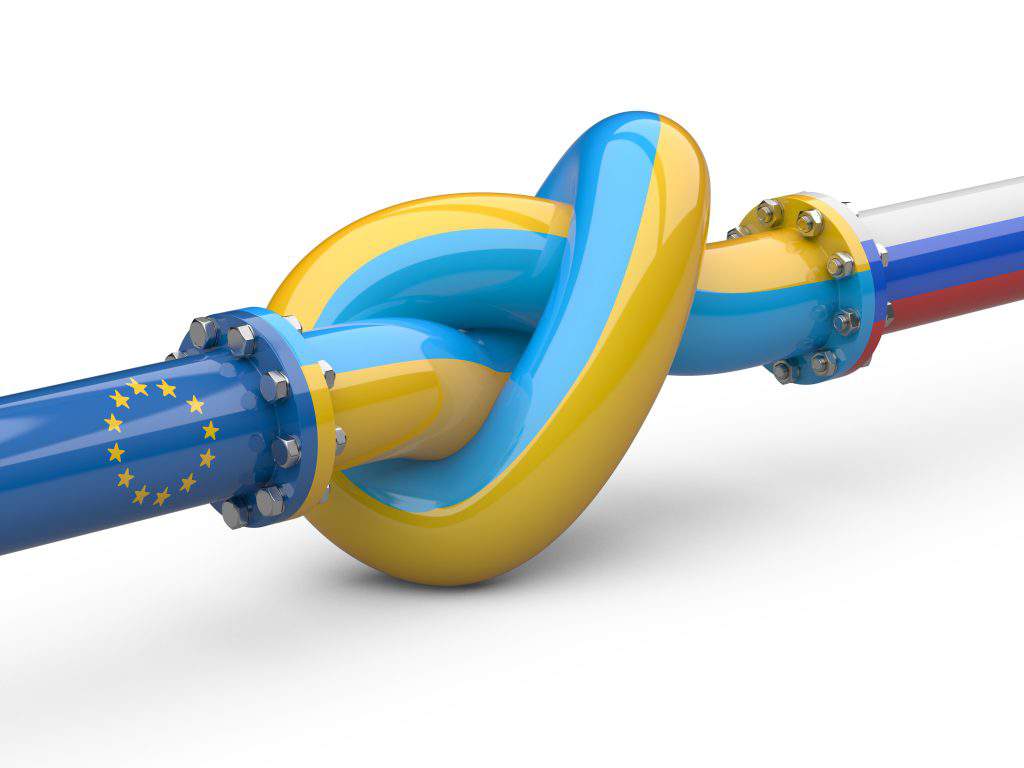

Most energy experts are calling 2019 a critical year for Ukraine. If there is no miracle and the good European fairy does not wave her magic financial wand and shower Kiev with gold in the next few months, the rusty pipes of the old Ukrainian gas pipelines will remain useless scrap metal, spoiling the country’s natural and economic landscape.

It has long been no secret that the Ukrainian gas transmission system (GTS) is in a catastrophic condition: according to various assessments, the resources needed to repair and modernize it could exceed $10-12 billion. It is well known that figures can be confusing, but no one has yet come up with a better way of identifying pros and cons than simple arithmetic. Ukraine’s GTS is a prime example of where a few figures make everything clear. And so, if official statistics are to be believed, around 20 thousand kilometres of the country’s gas pipelines have already been in use for more than 30 years, and around 13 thousand kilometres for more than 15 years. 90% of compressor stations have been in service for more than 25 years, and these are currently less than 30% efficient.

Ukrainian experts themselves have long sounded the alarm and are very sceptical in their assessment of both their gas transmission industry and Kiev’s prospects of playing any part at all on the main European stage in the near future.

“There is a very real threat that we will cease to be considered a geopolitical player. In 2019, Ukraine’s contract with Russia to transport gas will come to an end. Unfortunately, our crumbling gas transmission system will by then reach a critical condition without modernization: the equipment has undergone natural ageing over 40 years. This will automatically lead to a lack of new contracts. As a result, the country will lose its transit status – the only trump card that has helped it influence geopolitical processes. This is a colossal blow to national security,” said Vadim Karasev, Director of the Ukrainian Institute of Global Strategies, sounding the alarm some time ago. After just months, these words now appear prophetic.

But if the worries of experts in Ukraine itself are first and foremost linked with the fact that Kiev is losing the status of a serious player on the region’s geopolitical stage, other analysts are understandably more worried by the collapse of Ukraine’s GTS from a purely economic point of view.

Mark Goichman, leading analyst at the TeleTrade company elucidates his fears by explaining that Ukrainian gas pipelines will remain profitable for the country only if at least 60 billion cubic metres (bcm) of gas flows through them each year. While transit to Europe is more than 90 bcm, the problem of preserving and modernizing the GTS is current. But if Russia completes construction of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline and brings it to its rated capacity, transit will fall significantly, to 10-15 bcm.

As far as the repair and maintenance of the Ukrainian GTS is concerned, even the most modest assessments by Western experts say it will take €3 billion to “patch up the holes.” A fullscale renovation of Ukraine’s gas transmission infrastructure will require €10 billion. Accepting the likelihood that Russian gas transit volumes will fall, even by 50%, any investment would prove senseless as the system will still become unprofitable.

Even if the European Commission is able to put the brakes on construction work on the Baltic Sea bed by adopting the new Gas Directive or through delays issuing a permit to lay the pipe in Denmark’s territorial waters, this will not solve the problem: Russia has already announced that it is accelerating work on the planning and construction of yet another gas pipeline – TurkStream. It is hardly likely that Western mediation will succeed in finding a formula by which Moscow would help the new authorities in Kiev and agree to maintain transit in its former volumes.

A vicious circle is forming, warns Mark Goichman. On the one hand, without enormous investment in the GTS, it will inevitably become completely unfit for use within a few years. On the other, such investment will probably not happen, as Kiev has no domestic resources, and previous external credits for the GTS were spent mainly on other purposes – or simply stolen. It is precisely the sorry state of the GTS that for purely technical reasons creates a perceptible and constant threat of interruptions to the gas supply to the EU through Ukraine. Therefore, Europe is hardly likely to turn down alternative options in the medium term; these include Nord Stream 2, whose construction is now nearly complete, and which will have a capacity of 55 bcm a year.

The lamentable result of previous financing for the modernization of the Ukrainian gas pipeline networks is precisely what is causing doubt about the effectiveness of further investment. The Europeans would perhaps be happy to invest more money in Ukraine, in order once more to spite Vladimir Putin, but his Ukrainian opposite number, Petro Poroshenko, is about to face presidential elections and does not seem to know himself what he wants. The state Naftogaz company would otherwise be behaving differently. It is however avoiding providing its European partners with detailed information about the real state and limits of the operational resources of the national GTS. In this context, many experts are linking the company’s unwillingness to carry out complex testing of the system with the widespread practice of illegal tapping into gas pipelines.

The Ukrainians are trying somehow to patch up the holes in the GTS themselves, but their investments are based only on the necessity of modernizing the main pipelines going west, along which a reverse supply of fuel from Europe could be arranged in the future. The question of financing other routes has been postponed until the situation with Russian gas transit after 2019 has been resolved. Kiev is tying foreign partners’ entry to a management consortium for the GTS with major investments in the system. The Ukrainian authorities are unhappy that potential members of the consortium are only prepared to operate the part of the system that provides the flow of Russian gas to Europe. However, not one of the potential Western investors has so far wished to acquire a share in Ukraine’s gas transmission system; this has forced the government to end preparations for a competition for the sale of the GTS.

The majority of analysts agree that Kiev has essentially halted reform of Ukraine’s energy sector at present, for Petro Poroshenko’s electoral reasons. The government has put equalization of gas prices for domestic and industrial consumers on ice. A potential victory by Yulia Tymoshenko in the presidential elections does not add to optimism about the reform of the Ukrainian gas industry. Tymoshenko has always questioned the expediency of foreign involvement in the management of the national GTS. Experts assume reasonably that as head of government, she would be driven in this area by corporate and crony interests rather than common European ones.

At any rate, Tymoshenko does not look like the fairy with the magic financial wand – Poroshenko even less so. As a serious branch of the economy, the Ukrainian gas transmission system is probably akin to Pompeii – counting on an unexpected miracle rather than facing the likelier reality.