Germany long ago decided to abandon nuclear power, but international momentum and the energy lobby are calling the rationality of this decision into question. The CDU party led by Friedrich Merz, which won Germany’s federal elections in February 2025, has started talking cautiously about reviving nuclear power plants. So how irrevocably has Germany embarked on a path away from nuclear power? Are there financial and political costs that could deflect the country from this path?

In February, Germany held early parliamentary elections that swept a coalition of Social Democrats, Greens and Liberals from power. Five parties were elected to the Bundestag, with the conservative bloc of the Christian Democratic Union and the Christian Social Union (CDU/CSU) winning first place with 28.5% of the vote and 208 seats in the Bundestag. Despite this, the result was the bloc’s second worst in the country’s post-war history. CDU leader Friedrich Merz has said he plans to form a government by Easter, which falls on 20 April.

This victory, uncertain as it is, raises the logical question of future changes in the politics and economy of a country weathering a perfect storm of economic slowdown, geopolitical contradictions with adversaries and allies, high energy prices, and the consequences of its categorical rejection of options such as coal and nuclear power. The issue of nuclear power is particularly high on the agenda because while it is enjoying a new boom around the world, in Germany the issue is highly controversial.

Protracted exit

Following the nuclear accident at Japan’s Fukushima power plant in 2011, which shocked the world, Chancellor Angela Merkel’s government made the historic decision to begin the process of abandoning nuclear power altogether.

Germany’s abandonment of nuclear power was politically complex, particularly because the planned closure of the country’s last remaining power plants coincided with the 2022 energy crisis. Eight units were immediately shut down back in 2011: these were Biblis A and B, Brunsbüttel, Isar 1, Krümmel, Neckarwestheim 1, Phillipsburg 1 and Unterweser. The Brokdorf, Grohnde and Gundremmingen C nuclear power plants were finally shut down at the end of December 2021. The country’s last three units – Emsland, Isar 2 and Neckarwestheim 2 – were closed in April 2023. All the plants are now at various stages of the long decommissioning process, particularly because a decision has still not been made about what to do with the waste.

Since then, politicians have been trading accusations over what should have been done differently in the process and by whom. In 2024, a parliamentary committee set up by the conservatives even investigated allegations that economy minister Robert Habeck, a member of the Green Party, was insisting on the permanent closure of nuclear power plants based on his party’s ideology and ignoring the issue of the country’s energy security.

The development of renewable energy sources should have been a silver bullet and compensated for the forced abandonment of nuclear energy, but this did not happen. Wind energy has been developing slowly in Bavaria, and the expansion of power line capacity in southern Germany has also progressed more slowly than planned. Satisfying demand for electricity in Germany has therefore required ever more fossil fuels or imports – mainly of French nuclear energy. A number of experts believe there is a certain paradox in importing nuclear energy from France. This lies in the fact that the nuclear power stations are just across the border and reactors in Germany itself could produce the same power, saving millions of euros.

International success

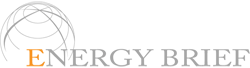

It must be said that while Germany continued to scrap nuclear projects, the rest of the world moved in exactly the opposite direction. In a recent report, the International Energy Agency (IEA) stated that the world’s nuclear power industry is experiencing a renaissance. 2024 saw a record 33% increase in nuclear capacity globally compared to the previous year. The record may be broken in 2025, although this depends on investment. The IEA predicts the increase will remain steady right up to the middle of the century.

The main proponent of responsible nuclear energy management, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), has repeatedly addressed the fate of nuclear power in Germany. In a recent interview with news agency dpa, for example,

IAEA chief Rafael Grossi indicated his view that a return to nuclear power in Germany would be reasonable. “I think it’s logical. It’s a rational position,” Grossi said, noting that Germany is the only country in the world to have completely abandoned nuclear power. Even Japan continues to use atomic energy, albeit more cautiously following the Fukushima nuclear accident. In addition, Grossi suggested that some countries that had previously moved towards abandoning the atom are beginning to think again about developing their nuclear projects. He noted that Germany is going through a difficult period economically, which is why some parties are calling for a return to nuclear power.

Adobe Stock: #1357896338

This “difficult period” for Germany has both economic and political implications, and it is not yet clear which path the country will choose in the coming months.

What could the new government’s energy policy be?

With regard to the CDU/CSU’s energy and climate policy, analysts do not for now expect a dramatic change of course from that of the previous government, as these issues were not key during the parties’ electoral battle. While climate protection was one of the most important issues in the 2021 election campaign, economic and foreign policy topics have now taken centre stage.

According to the CDU/CSU election programme, the bloc is committed to the goal of climate neutrality by 2045, but intends to reshape the path to achieve it. “Climate protection requires a strong economy,” stated its election programme. The CDU/CSU therefore wants to make electricity cheaper, but so far the most commonly heard ideas among measures announced are tax cuts and reducing network charges. In order to achieve the goals of the “energy transition,” the development of energy grids will be realised through cheaper overhead lines instead of expensive underground cable laying. In addition to wind and solar energy, the parties also call for more intensive use of biomass and geothermal energy.

With regard to nuclear energy, Friedrich Merz’s statements are more ambiguous, leaving room for speculation and public debate. In particular, during the election campaign he stated that the original policy of abandoning nuclear energy was a “serious strategic mistake.” But at the same time, he said it was “most likely” impossible to reverse the dismantling of nuclear power plants in Germany. Merz added that the likelihood of reactivating the plants is “decreasing every week.” The CDU chief’s admission that nuclear power in Germany is probably dead comes despite a pledge in his party’s election programme to explore “the possibility of reactivating recently closed nuclear power plants.” This could, among other things, save Germany from its growing dependence on electricity imports from France.

The CDU programme also mentioned “research into fourth and fifth generation nuclear power, small modular reactors and fusion power plants.” While this would seem to leave a glimmer of hope for supporters of nuclear power in Germany, the likelihood of such technologies becoming viable for energy production is not obvious. Not only are they expensive or controversial: it would simply take a lot longer. The party has yet to comment on whether it has changed its position following Merz’s remarks.

Voices in the wilderness

In early March, the German nuclear lobby group Kerntechnik Deutschland eV (KernD), which includes subsidiaries of Westinghouse and Framatome, as well as the partly German nuclear engineering services company Nukem and other companies, said that several closed nuclear power plants in Germany could “theoretically” be reopened. The lobbyists’ view is that “uncompetitive electricity costs” threaten the very existence of the German economy.

“The recommissioning of up to six nuclear power plants is technically possible … The quicker the decision is made, the less money it costs and the sooner the baseload-securing, climate-friendly plants can rejoin the grid,” the KernD group said in a statement. It also estimated the investment needed for this to happen at between €1bn and €3bn.

The document also states that “if the proportion of volatile energy sources in the German energy mix continues to increase, the need for electricity imports or self-generated fossil electricity will intensify. This is a vicious circle that will lead to disastrous dependencies.” KernD notes that the continued operation of coal-fired power plants has resulted in significantly higher carbon dioxide emissions than planned, and that the coal phase-out schedule, which has already been revised in recent years, is “unrealistic” under current conditions.

In a statement, the group summed up its view that “the recommissioning of nuclear power plants in Germany is [a] pragmatic, economical and socially sensible solution.”

Interestingly, the statement was released a day after the CDU/CSU and the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), which want to form a coalition government, agreed to create a €500 billion infrastructure fund and to revise borrowing rules as part of a major spending overhaul to reorganise the military and revive growth in Europe’s largest economy. As yet, there are of course no specifics on the projects that may receive funding from the fund.

Imagining a nuclear future

But what will the return of nuclear plants mean for the economy in practice? On the one hand, it will ensure the introduction of a large installed capacity of electricity generation within three to five years. This would accelerate the phase-out of coal-fired generation without jeopardising the security of the economy’s energy supply or Germany’s climate ambitions. Nuclear power would also lead to sustainably lower prices (the premium in Germany over prices in neighbouring France is in the tens of euros) and increased stability of the energy system due to the ability of nuclear power plants to balance the volatile nature of renewables. Thus, it would indirectly allow further development of wind and solar power.

Adobe Stock: #1296747577

On the other hand, former operators of German nuclear power plants have reacted with criticism to the idea of suspending the dismantling process. Thus, they pointed to their legal obligations to ensure a rapid dismantling. Energy company E.ON, owner of the Isar 2 plant, argued that “anything is possible” as restarting the plants would be “primarily a political issue.” However, it also said that “it is clear that this will be very difficult from a technical and regulatory point of view” and will take many years to realise. Another former operator, RWE, said that restarting the nuclear reactors would involve “significant regulatory, financial and personnel obstacles.”

German nuclear energy critic Mycle Schneider, coordinator of the World Nuclear Industry Status Report, said that recommissioning old nuclear reactors would be virtually equivalent to commissioning new ones because of the numerous technical requirements for modern plants, which would make little economic sense. Thus, from a business perspective, a return to nuclear power looks like a very expensive and incoherent endeavour. As well as former operators, other analysts and researchers have also expressed doubts about the feasibility and benefits of such a step, which would be a long process full of legal uncertainty, public and political resistance, and very high investment costs.

One should not forget the political side of the issue: the most likely junior partner in the future coalition, the SPD, remains committed to withdrawal from nuclear energy.

Thus, Germany’s most likely new chancellor, Friedrich Merz, will be faced with a serious dilemma on the issue of nuclear energy, and no one solution seems to be unequivocally correct now. On the one hand, Germany could synchronise with many other developed countries and bring back nuclear power for the sake of the stability of its energy supply and the strengthening of its economy. On the other hand, this would require a certain political shift, huge investments, overcoming a public backlash, and creating mechanisms that would protect the nuclear power industry from shifting political winds if the country is led by a representative of a different political force in four years’ time.

Experts note that if the political will exists, the new chancellor could follow the same path as that taken when bankrupt energy company Uniper was bailed out. Closed nuclear power plants could be transferred to state ownership so that businesses do not have to bear additional financial costs. A programme of reprivatisation of nuclear assets could later be scheduled. Whatever the case, one thing alone is clear today: the active debate on the fate of the atom in Germany will continue and it will not be possible to find a compromise quickly without strong political will.