In 2025, the European Union crossed a historic threshold. For the first time, electricity generated from wind and solar surpassed output from all fossil fuels combined. Renewables accounted for 30 percent of total EU electricity generation, compared to 29 percent from fossil fuels. Within this shift, solar energy is becoming more prominent with each passing year. But is Europe ready to rely more heavily on the world’s most powerful energy source – the Sun – effectively cutting out the middleman?

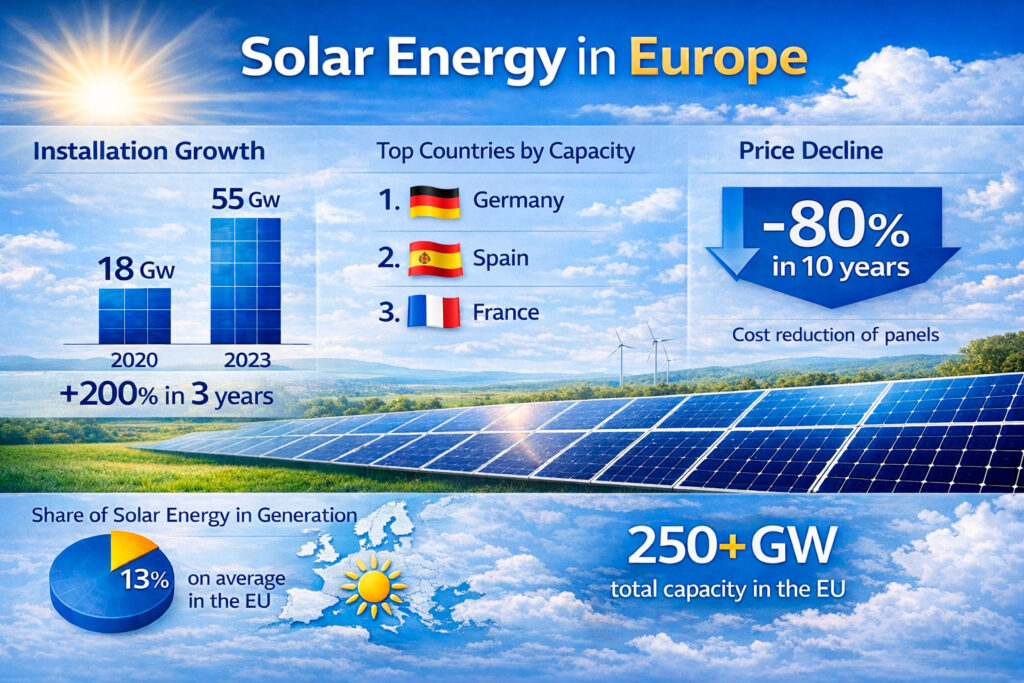

The numbers from 2025 tell a clear story. Solar power accounted for a record 13 percent of the EU’s electricity generation, surpassing both coal and hydropower over the same period. “Solar is now delivering for Europe,” said Walburga Hemetsberger, CEO of the European solar PV industry association. A symbolic peak was reached in June 2025, when, for the first time in history, the sun became the EU’s single largest source of electricity for an entire month.

Growth has been widespread. All 27 EU member states generated more solar electricity in 2025 than in the previous year. It was the fourth consecutive year in which total solar generation increased by more than 20 percent. Countries such as Hungary and the Netherlands as well as sunnier states like Greece and Spain already derive more than 20 percent of their electricity from solar power.

This momentum is largely driven by the rapid expansion of solar PV capacity across the continent. Total installed solar PV capacity in the EU reached an estimated 406 gigawatts in 2025, comfortably surpassing the bloc’s strategic target of 380 GW set out in the EU’s Solar Energy Strategy.

At the same time, solar PV has become one of the most competitive sources of electricity in many parts of Europe. Dramatic cost reductions: around 70 percent for new installations since 2010 have transformed solar from a purely environmental choice into one of the most economical options for power generation.

Public acceptance has also played a crucial role. Unlike wind turbines, solar panels can be installed on previously unused spaces such as rooftops. According to analysis by the Joint Research Centre (JRC), more than half of newly installed solar capacity in the EU is now located on rooftops. This brings energy generation closer to end users without issues such as noise or visual disturbance, which sometimes complicate wind power projects. Despite this progress, significant potential remains untapped: only about 10 percent of European roofs are currently equipped with PV systems.

Yet despite its rapid rise, solar energy still faces technical and industrial challenges that could slow its path toward becoming a central pillar of EU energy security. The EU aims for solar to supply at least 40 percent of its total electricity demand in the coming decades. Reaching that level from today’s 13 percent will be challenging, especially as electricity demand is expected to more than double due to electrification of transport, heating, and industry.

Meeting this goal will require more than installing solar panels on every rooftop across the EU’s estimated 271 million buildings. Organizations such as The Nature Conservancy advocate “smart siting” strategies, using detailed land-use mapping to locate large-scale solar farms on brownfields and degraded land, thereby minimizing environmental and social conflict. “In June we provided more power than any other source in the EU. It is now critical that policymakers implement robust frameworks for electrification, system flexibility, and energy storage to ensure solar leads Europe’s energy transition for the rest of this decade,” Hemetsberger emphasized.

Once electricity is generated, it must also be used and distributed effectively. Solar output is inherently uneven: generation drops to zero at night and declines significantly in winter, when demand is typically higher. Storage and redistribution therefore become essential. Europeans are increasingly deploying innovative solutions. While lithium-ion batteries dominate short-term storage, technologies such as solid-state batteries, liquid metal batteries, and improved pumped hydro are crucial for longer-duration storage. According to Beatrice Petrovich, a senior energy analyst at Ember, “In 2025, we saw the first signs of large-scale battery use extending renewable electricity into hours traditionally covered by gas.”

Grid infrastructure is another critical piece of the puzzle. Integrating variable renewable energy such as solar requires a fundamental rethinking of grid operation. In a 2024 assessment, the International Energy Agency outlined six stages of variable renewable integration, noting that only a few European regions — including Denmark — have reached advanced levels. Challenges range from improved forecasting and dispatch optimization to maintaining grid stability without relying on conventional power plants, all while avoiding sharp increases in electricity prices.

Technological progress alone will not be sufficient. The IEA and other experts stress that successful integration of high shares of variable renewables depends as much on regulatory reform as on innovation. Key measures include redesigning electricity markets to reward flexibility and storage, introducing non-price criteria in renewable auctions to support community benefits, and accelerating permitting through designated Renewable Acceleration Areas.

Taken together, solar energy is no longer a niche or symbolic element of Europe’s energy transition. It is already reshaping power markets, infrastructure planning, and policy priorities. The next challenge lies in transforming record-breaking generation into a stable and reliable backbone of the electricity system. By investing strategically in storage, modernizing grids, strengthening domestic manufacturing, and implementing forward-looking regulation, the EU can ensure that solar power becomes not only a leader in name, but the resilient and intelligent cornerstone of the world’s first climate-neutral continent.