Europe’s decarbonisation drive puts pressure on Poland’s coal industry, but new technologies could transform “black gold” into a valuable input for steel, chemicals, and regional supply security.

After the closure of Czechia’s last hard coal mine (CSM/ČSM in Stonava) in early 2026, Poland now remains the only EU country still mining hard coal on a significant scale. In European media, the Polish mining industry is often portrayed as a necessary evil. But could it, under certain conditions, become a strategic asset rather than a liability?

Poland’s Coal Debate – In Brief

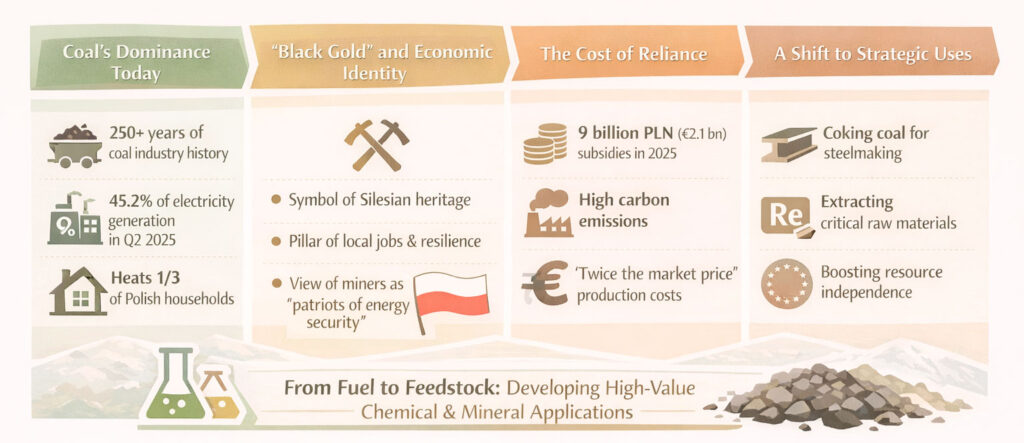

Poland’s coal industry is over 250 years old. Yet for many citizens, it is not a story of the past but of the present. A large number of households and businesses still rely on coal on a daily basis. Despite efforts to reduce coal’s share in the national energy mix, it c continues to generate a substantial portion of Poland’s electricity and heat roughly one-third of homes.

According to the Warsaw-based think tank Forum Energii, coal’s share in electricity generation fell below 50% only recently, reaching 45.2% in the second quarter of 2025. This marked a symbolic turning point in Poland’s gradual energy transition.

However, in Poland coal is not merely a fossil fuel. It is often referred to as “black gold” – the resource that powered the country’s industrial development during the communist era. In regions such as Silesia, coal mining represents a multigenerational identity and is closely associated with economic resilience and national sovereignty. As Brussels intensified calls for greater European energy independence, many Polish miners perceived themselves as part of the solution rather than the problem.

AI-generated

The political landscape reflects this tension. While the European Union is pushing for a comprehensive phase-out of coal, the domestic coal lobby remains influential. Trade unions and industry representatives argue for preserving mining operations as long as possible. Following negotiations between miners’ unions and successive governments, the current schedule foresees the gradual closure of hard coal mines by 2049.

However, this level of reliance comes at a significant financial, environmental and political cost. The sector largely survives due to substantial public subsidies. According to Notes from Poland, the state will provide 9 billion zloty (2.135 billion EUR) in support in 2025 (and 5.5 billion zloty – 1.3 billion EUR in 2026). Tobiasz Adamczewski, Vice President of Forum Energii, notes: ‘This is equivalent to roughly 10% of personal income tax revenues. Currently, the cost of coal production in Poland is almost twice its market price”.

As a result, Polish electricity remains among the most carbon-intensive in the EU. With the Union accelerating its decarbonisation agenda, several member states have expressed frustration over Poland’s continued reliance on coal.

Public debate, however, focuses primarily on coal’s role in electricity generation. Less attention is paid to its potential industrial applications. This article argues that phasing coal out of energy production while developing its use in high-value industrial processing – particularly in the chemical sector – could offer a strategic, rather than purely sentimental, pathway for preserving parts of Poland’s coal industry.

Coal to Chemicals And Critical Minerals

Moving beyond combustion, one potential avenue for restructuring Poland’s coal sector lies in high-value chemical production. This would represent a paradigm shift – from viewing coal solely as a fuel to recognising it as an industrial feedstock.

“Technological advances mean that sites once considered uneconomic may now prove to be valuable sources of sought-after metals,” says Dr. Alicja Kot-Niewiadomska of the Mineral and Energy Economy Research Institute of the Polish Academy of Sciences, in a comment to the Polish news outlet Fakt.

First, hard coal is a primary input for coke production – an essential material for blast furnace steelmaking. Coke production remains concentrated in Silesia, Poland’s industrial heartland. Although hydrogen-based steelmaking technologies are being developed across Europe, blast furnace production still dominates. As long as this remains the case, securing a stable, non-Russian source of high-quality coking coal could be viewed as a strategic asset for European industry.

Second, and more forward-looking, is the potential extraction of critical raw materials and rare earth elements from coal deposits and mining waste. The European Union lists 34 critical raw materials essential for advanced technologies such as batteries, electronics, defence systems, and renewable energy infrastructure. Many of these materials are heavily imported from China, prompting the EU to diversify supply chains and strengthen domestic production.

While controversial projects in Greenland illustrate the geopolitical urgency of securing such materials, coal seams and associated waste streams may also contain economically relevant quantities of critical elements.

Foreign companies have shown growing interest in Poland’s potential in this area. The Ukrainian company Coal Energy has explored investment opportunities, while Canadian firm Mkango and Grupa Azoty Puławy are developing a rare earth separation project in Puławy in Poland.

Krzysztof Galos, Poland’s Chief National Geologist and a member of the European Critical Raw Materials Board, states: “Due to the length of investment processes, especially in the mining sector, the effects will not be immediate. However, they may prove significant in the medium term. We need to increase extraction, processing and recycling of critical raw materials within the EU, diversify supply routes, and build adequate strategic reserves.”

Such a model would shift the coal sector’s focus from volume to value. Instead of defending coal as an energy source, Poland could reposition selected mining activities within the framework of EU strategic autonomy in raw materials. This approach would not preserve the industry in its traditional form – but it could provide a more economically rational and geopolitically aligned basis for maintaining mining expertise, infrastructure, and regional employment.