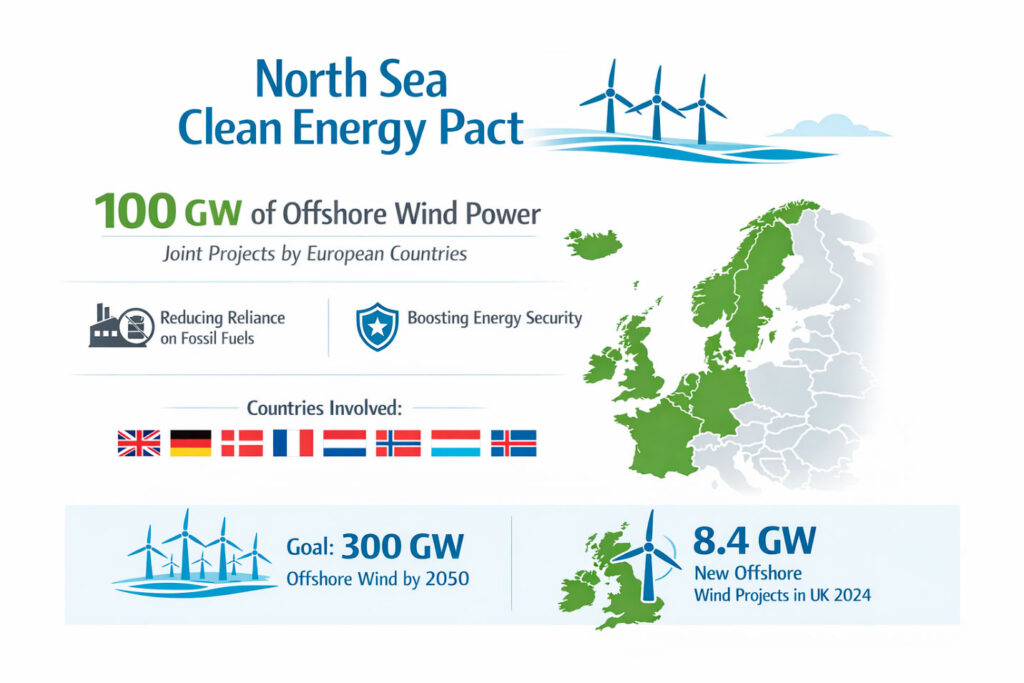

The North Sea is set to become Europe’s energy and protection zone. In Hamburg, nine countries signed a joint agenda: by 2050, 300 gigawatts of offshore wind power are to be generated in the North Sea, much of which will come from cross-border projects. At the same time, new grid regulations and greater security for critical infrastructure are under discussion.

For the third time in just a few years, the North Sea has taken centre stage in European energy and security policy. On 26 January 2026, the heads of state and government, along with the energy ministers, of several North Sea coastal states met in Hamburg. The aim was to strengthen cooperation on expanding offshore wind energy and, at the same time, to enhance the protection of critical infrastructure. The meeting was hosted by Federal Chancellor Friedrich Merz and Federal Minister for Economic Affairs and Energy Katherina Reiche.

The summit marks a turning point: wind is no longer discussed solely in terms of climate protection, but increasingly as a form of strategic infrastructure comparable to pipelines, ports and data cables. Accordingly, the agenda was broad, covering everything from energy policy and industrial issues to security and defence.

A summit that shaped history

The North Sea Summit began with the meeting in Esbjerg, Denmark in 2022, and continued with the meeting in Ostend, Belgium in 2023. Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine dominated both meetings, exposing Europe’s dependence on fossil fuel imports – especially Russian gas – and triggering a strategic shift.

Since Esbjerg, the basic idea has been to transform the North Sea into a shared European energy area. Rather than pursuing individual national projects, countries should coordinate their plans, develop networks together, and adopt a transnational approach to large offshore wind farms. However, Hamburg is now facing new challenges in the form of rising costs, stalled tenders and growing security risks, forcing a readjustment.

2050: Big Goals, Bold Future

The meeting focused on how to implement the ambition, reaffirmed in Ostend, to build 300 gigawatts of offshore wind capacity in the North Sea alone by 2050. This would be many times the current installed capacity and would cover a significant proportion of Europe’s electricity needs.

The signatories of the ‘Hamburg Declaration’ also committed to achieving up to 100 gigawatts of this target through cross-border cooperation projects. These projects include wind farms, grid connections and substation platforms that supply several countries simultaneously, known as hybrid or joint projects.

Another key topic was financing. Industry and government representatives advocated an investment approach that would provide decades of planning security. This would require ports to be expanded, special ships to be ordered, and industrial supply chains to be stabilised. In this context, WindEurope, the European wind energy industry association, speaks of an investment pact worth several hundred billion euros.

Why cooperation matters more than isolated solutions

The central theme of the summit is moving away from isolated national solutions. Until now, many countries have planned offshore wind farms primarily from a national perspective, with each country having its own grid connections, tendering rules and technical standards. This drives up costs and makes investment more difficult.

Going forward, therefore, spatial planning, tenders and grid development are to be coordinated more closely. Joint project pipelines should enable the industry and its investors to plan for the long term. Approval procedures are also a key focus, as they are often considered too slow and complex to facilitate the necessary expansion at the planned speed.

Another strategic issue is coupling offshore wind with green hydrogen production. Wind power could be used directly at sea for electrolysis and transported ashore via pipelines, which would benefit energy-intensive industries in north-western Europe in particular.

Political context

The political context in Germany is noteworthy. The federal government is not considered to be in favour of wind power. In November 2024, Chancellor Merz appeared on the ARD programme “Caren Miosga”, where he described wind turbines as “ugly” and suggested that they could one day be dismantled because they do not fit into the landscape. He also described wind power as a transitional technology.

Offshore installations are less affected by this criticism as they are located far from the coast. Nevertheless, Germany’s commitment to achieving its expansion targets is being closely monitored. The offshore sector is under pressure: in 2025, a tender for offshore areas received no bids for the first time. Rising costs, high risks, and uncertainties regarding grid connection are deterring investors.

Consequently, there was open discussion about the need for reform in Hamburg. The aim is to design tenders in such a way that they remain economically viable while ensuring that expansion targets are met.

Energy and security – two pillars of one strategy

The North Sea Summit also deliberately emphasises security policy. The Hamburg Declaration acknowledges the growing threat of sabotage, cyber and hybrid attacks on maritime energy infrastructure. Pipelines, power cables and data lines on the seabed are increasingly considered vulnerable.

This means that the North Sea is not only an important energy location, but also a key area for security policy. Accordingly, the exchange of security-related information is to be intensified, as is the protection of critical infrastructure – in close coordination with NATO.

Among those present was Jean-Charles Ellermann-Kingombe, NATO Assistant Secretary General for Cyber and Digital Transformation. “Today you cannot discuss energy without security. Energy is a target… So protection – physically as well as in cyber space – of the energy infrastructure as well as reliance on resilient supply chains need to be at the heart of the conversation when new important investment decisions are being made.“ This clearly demonstrates that energy infrastructure is increasingly regarded as an essential component of collective security.

Side swipe from Washington

The summit also received international attention due to the US’s open criticism. Speaking at the World Economic Forum in Davos, President Donald Trump labelled countries that rely on wind energy as ‘losers’. This stance was met with strong opposition in Europe.

EU Commissioner Wopke Hoekstra, who oversees the EU’s climate agenda, highlighted the significant economic costs of climate change. Clean energy is therefore an investment in competitiveness, prosperity, and security. Recent energy crises have particularly demonstrated how costly dependencies can be. And the British Energy Secretary Ed Miliband explained: “We are standing up for our national interest by driving for clean energy, which can get the UK off the fossil fuel rollercoaster and give us energy sovereignty and abundance.”

Who was there

The “Hamburg Declaration” was signed by the heads of state and government of Belgium, Denmark, Germany, France, Ireland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway and the United Kingdom. Iceland participated as an observer. The summit was attended by more than 100 business representatives, including network operators, energy companies, port operators and suppliers They will play a decisive role in determining whether the countries actually implement their political goals.

A clear signal to Europe

Ultimately, the North Sea Summit sends a clear message: despite the high costs, industrial policy risks and geopolitical tensions involved, the participating countries are committed to expanding offshore wind energy on a massive scale. They now view this as not only a climate protection project, but also a strategic building block for energy sovereignty, industrial strength, and the resilience of critical infrastructure.

Whether these ambitious goals will be achieved now depends on whether words are followed by deeds in terms of investment, approvals and European cooperation. According to the participants, the North Sea is set to become the backbone of a new, interconnected energy system.